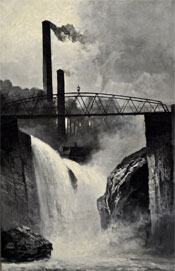

Upper Raceway Park

Selecting the Great Falls area as the first planned manufactory in the United States, the S.U.M purchased 700 acres of the area adjoining the Falls for a little over $8,000. The site had several positive attributes that made the land appealing for industrial development. Water was critical. The change in elevation could be transformed into hydropower. Existing streams could be diverted to create reservoirs that would expand lakes or ponds at the Passaic River’s headwaters. This would serve to retain a supply of water for dry seasons and could be used to regulate water flow. In addition, the site was near major shipping centers of northern New Jersey, New York, and Pennsylvania. Finally, the land near the Falls was fully developable and could be readily subdivided into sites that could be sold or leased for manufacturing.

Hamilton selected Pierre L’Enfant, a French-American architect and civil engineer who served with Hamilton during the Revolutionary War, to devise a plan that harnessed the water for hydropower. Hamilton admired L’Enfant’s visionary plan for Washington, D.C., which contemplated expansive growth of the federal government, and took almost 200 years to build out to completion.

Construction of a raceway system began in 1792, but L’Enfant’s initial plan for the raceway system proved too expensive and the S.U.M dismissed him, instead turning the project over to a New Englander with some industrial experience. Although delays and internal financial problems within the S.U.M. slowed the construction process, a successor to L’Enfant with practical engineering experience, Peter Colt, was successful in bringing waterpower to sites with a raceway system, using L’Enfant’s original plans. A system of waterwheels proliferated throughout the area and textile manufacturing was underway.

The S.U.M. made major additions and alterations to the raceway system throughout the first half of the 1800s. In its ultimate form, the raceway system was a three-tier system with Upper, Middle, and Lower Raceways capable of delivering over 2,000 horsepower. Designed this way, the system could take advantage of the drop in topography and re-direct water flow to all of the mill sites.

The raceways adapted and expanded over the first fifty years of Paterson’s history and were essential to the development of the area. As the President of the National Trust for Historic Preservation, Richard Moe, wrote in his testimony to the Senate advocating for the Paterson National Park, “Scholars have concluded that Pierre L’Enfant’s innovative waterpower system at the Great Falls—and many factories built later—constitute the finest remaining collection of engineering and architectural works representing each stage of America’s progress from Hamilton’s time to the 20th century.’’

Added in 1828, the Upper Raceway was the last piece of the system that the S.U.M. constructed. The raceway runs along a path behind Spruce Street from where you can view a number of the mills and historic factory buildings.

Added in 1828, the Upper Raceway was the last piece of the system that the S.U.M. constructed. The raceway runs along a path behind Spruce Street from where you can view a number of the mills and historic factory buildings.

Beginning with the first successful attempt within the United States to harness the entire power of a major river, Hamilton made Paterson a model of technological and engineering innovation. The abundance of inexpensive energy provided by the raceway system called many to Paterson, and those who came invented and produced goods that redefined the limits of life and changed our nation forever.

In 1977, the raceways were declared a National Historic Mechanical and Civil Engineering Landmark.

For an interactive tour chronicling the development of the raceway system and explaining its function in further detail, click here. The New Jersey History Partnership produced the tour using maps drawn by the U.S. Historic American Engineering Record.

THE MILLS

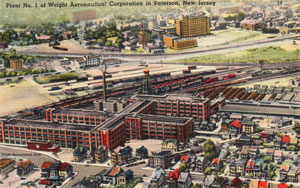

Although Paterson’s mills today look much like old red brick factories in any city, it was the work that took place within their walls that put Paterson at the cutting edge of “high tech” in the 19th century. When Hamilton founded Paterson, there was virtually no manufacturing anywhere in America. As Paterson grew, it became a business incubator for the American Industrial Revolution, much like California’s Silicon Valley is today for hot companies like Apple, Google, and Facebook.

Although Paterson’s mills today look much like old red brick factories in any city, it was the work that took place within their walls that put Paterson at the cutting edge of “high tech” in the 19th century. When Hamilton founded Paterson, there was virtually no manufacturing anywhere in America. As Paterson grew, it became a business incubator for the American Industrial Revolution, much like California’s Silicon Valley is today for hot companies like Apple, Google, and Facebook.

Paterson’s industrial achievements in the 18th and 19th centuries were the touchstone of many major components of the American industrial revolution. As a result of Hamilton’s efforts, Paterson became the most important American industrial site between the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812. During the earliest years of the city’s development, Paterson became the site of the first water-powered cotton spinning mill in 1794 and a candle wick spinning mill in 1800. A few years later, Paterson industrial entrepreneurs began manufacturing paper and soon invented machinery to make paper in one continuous sheet. Iron production also began in Paterson in 1800 and six new iron factories opened in the first quarter of the 19th century. Textile manufacturers built new mills in 1808 and 1809 and, by 1814, Paterson had more than ten mills processing some 1.5 million pounds of raw cotton. Between 1814 and 1829, seven more mills opened. The Paterson canvas industry boomed as naval contracts increased in an effort to provide a domestic supply in case of war. Paterson industrialists ventured into silk textiles in 1827, and their innovations in silk weaving made Paterson the largest silk producer in the world, earning it the label the “Silk City.”

Paterson led the nation not only in silk and other textiles but also in technology for security, transport, and machinery. Paterson is the birthplace of the Colt Revolver, the first American-made steam locomotives, and the first submarine. By 1854, Paterson was the largest producer of locomotives in America. The first submarine had its propulsion engine installed in Paterson and was first tested in the waters near the Great Falls. In the 19th century Paterson also became a world center for steel manufacturing and machinery production.

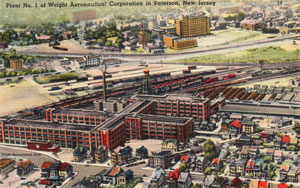

Progress continued during the 20th century. Paterson factories manufactured more aircraft engines than any city in the nation, including engines for bombers flown in World War II, as well as the engine for Charles Lindbergh’s Spirit of St. Louis, built at the Wright brother’s first plant in Paterson and the first airplane to complete a trans-Atlantic flight. In 1949, three sons of Paterson immigrant textile workers—Henry Taub, Joe Taub, and now United States Senator Frank Lautenberg—formed Automatic Data Processing, Inc. (ADP) in Paterson, and in the years that followed built the small business into a global company using electronic payroll and other technology to serve corporations and their employees around the world.

As the author Chris Norwood wrote in her book, About Paterson, “It is impossible to think of any other city whose products cut so deeply into the texture of the United States and not only transformed its national character, but revolutionized American relations with the world.”

For a National Park Service map of the mill district with additional educational teaching materials, click here.

Paterson’s Silk Industry and the “Modern Silk Road”

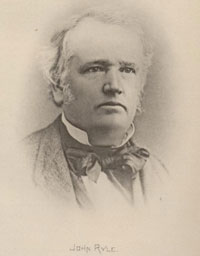

In his Report on Manufactures, Hamilton identified silk production as one of the most important products for American industry, a recommendation that would increase America’s involvement in international commerce. In the late 19th and 20th centuries, the silk mills of Paterson produced the largest amount of silk goods in the world. Led by John Ryle, immigrants from Europe came to Paterson, many with few possessions to call their own, and revolutionized the silk industry. By the 1870s, the industry came to dominate the city’s economy, and Paterson produced half of all silk made in the United States. At the height of Paterson’s silk production, there were approximately 121 firms in existence involved in every facet of silk manufacturing, and over 20,000 silk workers employed. The silk industry catapulted Paterson onto the international stage, helping to lead America into the global marketplace.

Paterson's central role in silk manufacturing formed a connection between America and the Asian, Middle Eastern, and European cultures that also cherished silk. As Richard Kurin of the Smithsonian Institution explains, “Silk both epitomized and played a major role in the early development of what we now characterize as a global economic and cultural system.” In the late 19th century, historians began to describe the old routes of the global trade of silk as the “Silk Road.” In recent years, historians at the Smithsonian and universities around the world have expanded the traditional view of the Silk Road and have recognized that the historical connection between East and West exists to this day.

In 1998 the cellist Yo-Yo Ma created the Silk Road Project, celebrating how people shared art and music along the modern Silk Road and promoting continued cultural collaboration between Asia, Europe, and the Americas. The Aga Khan, Imam of the Shia Imami Ismaili Muslims and direct descendant of Muhammad, has contributed generously to the Silk Road Project, particularly in the Muslim nations. Four years later, the Smithsonian organized—and the National Park Service cosponsored—the 2002 Folklife Festival to celebrate the modern Silk Road. The Aga Khan and Yo-Yo Ma joined Secretary of State Colin Powell in opening the festival. At the festival, Richard Kennedy of the Smithsonian Institute pointed out that since the tragic events of September 11, understanding the United States’ vital connection to the Silk Road has become increasingly more important, and that there is no better time “to celebrate the longstanding relationships that have existed between east and west and north and south.”

Paterson has the second largest Muslim population in America, and the Paterson National Park continues to be privileged with strong Muslim-American support. Dr. Alvin Felzenberg, a political scientist and an expert on New Jersey history, explains that Paterson is a station on the Silk Road not just because of its history as the “Silk City,” but also because of its strong Muslim population and the “large numbers of Islamic citizens who continue to work in Paterson textile businesses.” Dr. Felzenberg, who also served as the Principal Spokesman for the 9/11 Commission, writes that a Paterson National Park would create a connection between Muslims and the Park Service, while promoting valuable cultural interchanges between Muslims and other Americans.

Just as Paterson’s silk industry launched early American leaders into the global marketplace, Paterson’s place on the modern Silk Road will help prepare new generations of American leaders for global citizenship.

As the 20th century approached, electricity began to replace older technologies, but the Falls still remained important. On the riverbank just opposite the Falls, the S.U.M. constructed one of the country’s earliest hydroelectric plants in 1914, replacing the older waterwheels that had powered Paterson’s industries for 100 years. Situated on the bank of the river to take advantage of the natural geography, the plant generated hydroelectricity from the energy of the falling water, remaining operational until 1969.

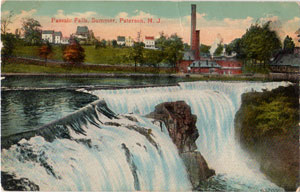

As the 20th century approached, electricity began to replace older technologies, but the Falls still remained important. On the riverbank just opposite the Falls, the S.U.M. constructed one of the country’s earliest hydroelectric plants in 1914, replacing the older waterwheels that had powered Paterson’s industries for 100 years. Situated on the bank of the river to take advantage of the natural geography, the plant generated hydroelectricity from the energy of the falling water, remaining operational until 1969. A National Natural Landmark since 1969, the Great Falls is at a chasm of basalt at a fault of the Watchung Mountain Range. At the end of the last Ice Age, about 13,000 years ago, the retreating glaciers recast the landscape around the Passaic River, which later carved a new route, deepening its canyon through the basalt and ultimately creating the cascade known as the Great Falls. Today, the 77-foot-high Great Falls pours up to two billion gallons into the basalt chasm daily, second in volume and width only to Niagara Falls in the eastern United States.

A National Natural Landmark since 1969, the Great Falls is at a chasm of basalt at a fault of the Watchung Mountain Range. At the end of the last Ice Age, about 13,000 years ago, the retreating glaciers recast the landscape around the Passaic River, which later carved a new route, deepening its canyon through the basalt and ultimately creating the cascade known as the Great Falls. Today, the 77-foot-high Great Falls pours up to two billion gallons into the basalt chasm daily, second in volume and width only to Niagara Falls in the eastern United States.

One of America’s most important 20th century artists, Oscar Bluemner, is known for his large colorful paintings and powerful charcoal drawings of Paterson silk mills, other factories, and the vibrating river waters below the Great Falls. A major show at the Whitney Museum of Art in New York in 2006 featured many Paterson paintings and sketches by this great American modernist, whose works have also been featured in The New York Times, the New Yorker, and the journal of the Smithsonian American Art Museum. Studies for one of his striking paintings of glowing red brick Paterson silk mills, entitled Jersey Silkmills, are in the Oscar Bluemner papers in the Smithsonian Institution Archives of American Art.

One of America’s most important 20th century artists, Oscar Bluemner, is known for his large colorful paintings and powerful charcoal drawings of Paterson silk mills, other factories, and the vibrating river waters below the Great Falls. A major show at the Whitney Museum of Art in New York in 2006 featured many Paterson paintings and sketches by this great American modernist, whose works have also been featured in The New York Times, the New Yorker, and the journal of the Smithsonian American Art Museum. Studies for one of his striking paintings of glowing red brick Paterson silk mills, entitled Jersey Silkmills, are in the Oscar Bluemner papers in the Smithsonian Institution Archives of American Art.  The Great Falls and Paterson’s historic factories have also influenced a number of great writers and poets, from 19th century author Washington Irving, whose only published poem was entitled, “The Falls of the Passaic,” to contemporary novelist Junot Díaz, who won a Pulitzer Prize for his bestselling novel, The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao. One of America's greatest poets, William Carlos Williams, penned the epic poem Paterson. Writing in the journal of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, Professor Roberta Smith Favis called the poem "an apt epigraph for Oscar Bluemner's paintings of the textile mills of Paterson. Williams echoed Bluemner's realization that this gritty New Jersey town could stand for the essence of America." Other writers who drew inspiration from the Falls include John Updike, whose novel, In the Beauty of the Lilies, was set largely in Paterson, and beat poet Allen Ginsberg, who grew up in Paterson and was greatly influenced by Williams, often referring to Paterson in poems and poetry readings throughout the world. "Renowned as the author of a 'dirty' poem whose first public reading in a West Coast gallery was said to have turned the 1950s into the '60s in a single night," wrote Walter Kirn in a 2006 essay for The New York Times, "Allen Ginsberg embodied, as a figure, some great cold war climax of human disinhibition."

The Great Falls and Paterson’s historic factories have also influenced a number of great writers and poets, from 19th century author Washington Irving, whose only published poem was entitled, “The Falls of the Passaic,” to contemporary novelist Junot Díaz, who won a Pulitzer Prize for his bestselling novel, The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao. One of America's greatest poets, William Carlos Williams, penned the epic poem Paterson. Writing in the journal of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, Professor Roberta Smith Favis called the poem "an apt epigraph for Oscar Bluemner's paintings of the textile mills of Paterson. Williams echoed Bluemner's realization that this gritty New Jersey town could stand for the essence of America." Other writers who drew inspiration from the Falls include John Updike, whose novel, In the Beauty of the Lilies, was set largely in Paterson, and beat poet Allen Ginsberg, who grew up in Paterson and was greatly influenced by Williams, often referring to Paterson in poems and poetry readings throughout the world. "Renowned as the author of a 'dirty' poem whose first public reading in a West Coast gallery was said to have turned the 1950s into the '60s in a single night," wrote Walter Kirn in a 2006 essay for The New York Times, "Allen Ginsberg embodied, as a figure, some great cold war climax of human disinhibition."  In the 1840s, the young immigrant and prominent Paterson silk manufacturer John Ryle purchased this piece of land, and built a reservoir where he could store water from the Passaic River to power his silk manufacturing site just across the river. The story of John Ryle’s road to success is one that could only happen in America. Orphaned at a young age in Macclesfield, England, he went to work in a British silk mill at the age of five, where he was known as a “bobbin boy.” After Ryle came to the United States at the age of twenty-two, he was able to manufacture America’s first skein of silk in Paterson by 1840. Ryle revolutionized the silk industry and led Paterson to become the largest silk manufacturing city in the world.

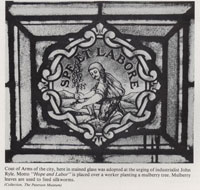

In the 1840s, the young immigrant and prominent Paterson silk manufacturer John Ryle purchased this piece of land, and built a reservoir where he could store water from the Passaic River to power his silk manufacturing site just across the river. The story of John Ryle’s road to success is one that could only happen in America. Orphaned at a young age in Macclesfield, England, he went to work in a British silk mill at the age of five, where he was known as a “bobbin boy.” After Ryle came to the United States at the age of twenty-two, he was able to manufacture America’s first skein of silk in Paterson by 1840. Ryle revolutionized the silk industry and led Paterson to become the largest silk manufacturing city in the world. Although he struggled on his way to the top, Ryle went on to serve as the city’s mayor in the late 1800s, remaining active in the business of silk manufacturing, and even conceiving Paterson’s city motto, “Spe et Labore” (Hope and Labor), which is still written on the Paterson coat of arms. Ryle will forever be known as the “Father of the Silk Industry.”

Although he struggled on his way to the top, Ryle went on to serve as the city’s mayor in the late 1800s, remaining active in the business of silk manufacturing, and even conceiving Paterson’s city motto, “Spe et Labore” (Hope and Labor), which is still written on the Paterson coat of arms. Ryle will forever be known as the “Father of the Silk Industry.” Added in 1828, the Upper Raceway was the last piece of the system that the S.U.M. constructed. The raceway runs along a path behind Spruce Street from where you can view a number of the mills and historic factory buildings.

Added in 1828, the Upper Raceway was the last piece of the system that the S.U.M. constructed. The raceway runs along a path behind Spruce Street from where you can view a number of the mills and historic factory buildings. Although Paterson’s mills today look much like old red brick factories in any city, it was the work that took place within their walls that put Paterson at the cutting edge of “high tech” in the 19th century.

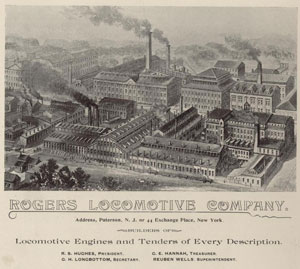

Although Paterson’s mills today look much like old red brick factories in any city, it was the work that took place within their walls that put Paterson at the cutting edge of “high tech” in the 19th century. The original Rogers factory buildings on both sides of Spruce Street near the Upper Raceway were used for cotton-spinning and producing textile-manufacturing equipment. But soon after the operation began, the company diversified and began producing locomotive parts to supply the budding U.S. railroad industry. Five years after opening operations on Spruce Street, the Rogers Locomotive company built a two-story locomotive erecting shop on the street’s east side, which now houses the Paterson Museum and offices on the corner of Market and Spruce Streets. The company completed its first engine, the Sandusky, at this site in 1837 and continued to produce locomotives here until 1913. In the 1870s, workers completed the assembly of up to three locomotives each week, a remarkable feat at the time.

The original Rogers factory buildings on both sides of Spruce Street near the Upper Raceway were used for cotton-spinning and producing textile-manufacturing equipment. But soon after the operation began, the company diversified and began producing locomotive parts to supply the budding U.S. railroad industry. Five years after opening operations on Spruce Street, the Rogers Locomotive company built a two-story locomotive erecting shop on the street’s east side, which now houses the Paterson Museum and offices on the corner of Market and Spruce Streets. The company completed its first engine, the Sandusky, at this site in 1837 and continued to produce locomotives here until 1913. In the 1870s, workers completed the assembly of up to three locomotives each week, a remarkable feat at the time. Rogers Locomotive Company produced locomotives for many railroad companies throughout the country, becoming the nation’s premier locomotive manufacturer in the mid-1800s. When the Golden Spike completed the Transcontinental Railroad in 1869, a Rogers Locomotive was there to link the nation. Of the 246 American locomotives used to build the Panama Canal, 144 were from Paterson. One of those was Old 299, which returned to Paterson in 1979 and can be seen at the rear of the Paterson Museum.

Rogers Locomotive Company produced locomotives for many railroad companies throughout the country, becoming the nation’s premier locomotive manufacturer in the mid-1800s. When the Golden Spike completed the Transcontinental Railroad in 1869, a Rogers Locomotive was there to link the nation. Of the 246 American locomotives used to build the Panama Canal, 144 were from Paterson. One of those was Old 299, which returned to Paterson in 1979 and can be seen at the rear of the Paterson Museum. Just past the buildings of Rogers Locomotive Works along the Upper Raceway path is the Dolphin Mill. The American Hemp Company, which specialized in spinning hemp into rope, erected the Dolphin Mill in the mid-1840s. In 1851, the Dolphin Manufacturing Company took over mill operations and began spinning jute, commonly known as burlap, and manufacturing multi-colored twisted jute carpeting. Originally, the mill was driven by a combination of water-powered turbines and separately housed steam engines; however, the installation of a sole 1200 horsepower engine in late 1901 eliminated the need for these outmoded power sources. The mill prospered for decades, and in 1881 the Dolphin Mill was the largest jute factory in the United States, with over 600 employees spinning 2,172 tons of jute annually.

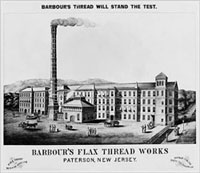

Just past the buildings of Rogers Locomotive Works along the Upper Raceway path is the Dolphin Mill. The American Hemp Company, which specialized in spinning hemp into rope, erected the Dolphin Mill in the mid-1840s. In 1851, the Dolphin Manufacturing Company took over mill operations and began spinning jute, commonly known as burlap, and manufacturing multi-colored twisted jute carpeting. Originally, the mill was driven by a combination of water-powered turbines and separately housed steam engines; however, the installation of a sole 1200 horsepower engine in late 1901 eliminated the need for these outmoded power sources. The mill prospered for decades, and in 1881 the Dolphin Mill was the largest jute factory in the United States, with over 600 employees spinning 2,172 tons of jute annually. Beside the Dolphin Mill is the Barbour Flax Spinning Company Complex. Thomas Barbour of William Barbour & Sons, a Scottish company that had been identified with the manufacture of linen thread in the flax mills of Scotland and Ireland for many years, came to Paterson in 1864 to establish an American branch of the family’s business. The Barbours immediately imported machinery from factories in Ireland to begin manufacturing flax yarns and threads. Flax weaving was an important industry in the mid-1800s and the mill was a major success.

Beside the Dolphin Mill is the Barbour Flax Spinning Company Complex. Thomas Barbour of William Barbour & Sons, a Scottish company that had been identified with the manufacture of linen thread in the flax mills of Scotland and Ireland for many years, came to Paterson in 1864 to establish an American branch of the family’s business. The Barbours immediately imported machinery from factories in Ireland to begin manufacturing flax yarns and threads. Flax weaving was an important industry in the mid-1800s and the mill was a major success. Beside the Rogers Administration Building, following the path away from the Upper Raceway and before crossing Spruce Street to enter the path along the Middle Raceway, you will come to the Ivanhoe Wheelhouse, the only building that remains of the once extensive Ivanhoe Paper Company. When in full operation, the Ivanhoe Mill was one of the earliest paper mills in the nation. The ten building complex was built to manufacture paper from cotton rags. Today, all that remains of the Ivanhoe Mill is the small handsome wheelhouse building constructed in 1865 that housed an 83 inch water driven turbine. The buildings once occupied the site that is now a Burger King and its parking lot.

Beside the Rogers Administration Building, following the path away from the Upper Raceway and before crossing Spruce Street to enter the path along the Middle Raceway, you will come to the Ivanhoe Wheelhouse, the only building that remains of the once extensive Ivanhoe Paper Company. When in full operation, the Ivanhoe Mill was one of the earliest paper mills in the nation. The ten building complex was built to manufacture paper from cotton rags. Today, all that remains of the Ivanhoe Mill is the small handsome wheelhouse building constructed in 1865 that housed an 83 inch water driven turbine. The buildings once occupied the site that is now a Burger King and its parking lot. If you continue along the Middle Raceway path, just before the Middle and Lower Raceways meet, you will come to the Hamilton Mill. This is among the oldest mills still standing from the days of the S.U.M. Erected by Henry Morris in 1814, the Hamilton Mill sits on the site of the original S.U.M. cotton mill. The Hamilton Mill operated as a cotton mill until Morris moved his operation to Pennsylvania, after which the new business utilized the mill for silk weaving and “throwing,” a process that twists the silk rather than spinning it like cotton and wool. Mill operations were discontinued after the Civil War. Tragically, a fire severely damaged the mill, but portions of the original brownstone walls and a section over the raceway were incorporated into new construction featuring mixed commercial and residential uses.

If you continue along the Middle Raceway path, just before the Middle and Lower Raceways meet, you will come to the Hamilton Mill. This is among the oldest mills still standing from the days of the S.U.M. Erected by Henry Morris in 1814, the Hamilton Mill sits on the site of the original S.U.M. cotton mill. The Hamilton Mill operated as a cotton mill until Morris moved his operation to Pennsylvania, after which the new business utilized the mill for silk weaving and “throwing,” a process that twists the silk rather than spinning it like cotton and wool. Mill operations were discontinued after the Civil War. Tragically, a fire severely damaged the mill, but portions of the original brownstone walls and a section over the raceway were incorporated into new construction featuring mixed commercial and residential uses. Franklin Mill

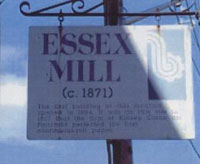

Franklin Mill Adjacent to the Franklin Mill on Mill Street near the corner of Van Houten Street is the Essex Mill, located on the first plot of land ever leased from the S.U.M. to private investors. In 1801, that first S.U.M. lease enabled Charles Kinsey, the mill’s first tenant, to draw enough water from the raceways to drive a budding paper manufacturing business. This first endeavor failed, but during the War of 1812, Kinsey replaced their paper business with textile production.

Adjacent to the Franklin Mill on Mill Street near the corner of Van Houten Street is the Essex Mill, located on the first plot of land ever leased from the S.U.M. to private investors. In 1801, that first S.U.M. lease enabled Charles Kinsey, the mill’s first tenant, to draw enough water from the raceways to drive a budding paper manufacturing business. This first endeavor failed, but during the War of 1812, Kinsey replaced their paper business with textile production. On the corner of Market and Spruce streets, the former Rogers erecting shop is now home to the Paterson Museum. Completed in 1871, the building was the final stop along a locomotive assembly process that stretched two and a half blocks. Here, workers completed the assembly of up to three locomotives each week in the 1870s—the heyday of the Rogers Company. Each completed locomotive would be wheeled out through a set of double doors, and the building could accommodate a dozen at once—this is why you can see twelve sets of doors on its Spruce Street front.

On the corner of Market and Spruce streets, the former Rogers erecting shop is now home to the Paterson Museum. Completed in 1871, the building was the final stop along a locomotive assembly process that stretched two and a half blocks. Here, workers completed the assembly of up to three locomotives each week in the 1870s—the heyday of the Rogers Company. Each completed locomotive would be wheeled out through a set of double doors, and the building could accommodate a dozen at once—this is why you can see twelve sets of doors on its Spruce Street front.